In chapter one of How To See The World by Nicholas Mirzoeff, titled “How to See Yourself”, the author begins by tracing the history and impact of the self-portrait from the era of the Spanish painter Velázquez in the seventeenth century to the modern “selfies” of today, all through various movements and technologies. Throughout the chapter, the author focuses on four main topics:

- The concept of Majesty and its transferal to the artist

- The self-portrait is a carefully controlled setting and can portray the artist however they wish to be seen

- The self-portrait can become a stage for political and social statements

- “Selfies” and self-portraits are made for a networked society

A Summary:

Previously only accessible to those with higher power, self-portraits available to the common class have revolutionized the idea of the “self-portrait”. These include the famed “selfie” which was even added to the Oxford dictionary. While usually separate from any official roles, the barrier between the official and unofficial was broken with selfies taken by world leaders at Nelson Mandela’s funeral, as well as on reality shows and other public broadcasts involving celebrities, such as the Ellen DeGeneres Show. However, the self-portrait has a much longer history.

Beginning with the example of Velázquez and his famous portrait “Las Meninas” in the seventeenth century, Mirzoeff explores the idea of “Majesty”, the persona carefully crafted by members of the ruling class to promote their image of infallibility, strength, and other qualities vital to their royal status and to ensuring they remained in power. Majesty in “Las Meninas”, Mirzoeff explains, begins with the incredible and new idea of placing all characters, including the artist himself, in a position which looks out at the audience, and, as the mirror in the background shows, at the king and queen, who occupy the same space as the audience. This awe at what they are looking at stems from the Majesty of the individuals before them, not necessarily the people themselves, but more than anything, what they represent.

This idea of Majesty slowly leaks onto the artist, as Velázquez paints himself with noble distinctions, and portrays an image of himself as royalty, as Mirzoeff explains later, becoming, in a sense, a hero. Later, during the nineteenth century, French court painter Vigeé Le Brun similarly transfers a royal air to herself in her own self-portraits, which not only speak to her skill as a painter, but also shows a striking similarity between her portraits of royalty; she is dressed in fine clothes and looks directly at the viewer on a similarly scumbled background, making her the primary viewing figure. In addition, she also painted Marie Antoinette in a very informal manner, which caused outrage at the time, but which mimicked the aforementioned painting, or vice versa, drawing the connection to royalty nearer and her personal style and representation closer to royalty. Le Brun also subtly mimicked, manipulated, and redefined the image of Madonna and Child by showing herself as a mother with her daughter in an era in which motherhood was not a celebrated ideal. This shows the ability of artists to change commonly held symbols and invent their own meaning to them.

This, in turn, leads to Mirzoeff’s second main point: that every self-portrait is a carefully staged appearance of what the artist wishes you to see and what they wish you to ignore. There is a narrative to portraiture, and the story can be assumed from it and staged to look a certain way. Toulouse-Lautrec, for instance, only showed the top half of his body in a mirror to prevent the viewer from seeing his disability, Courbet and Bayard posed to portray an artistic narrative through self-portrait, and every modern selfie is carefully constructed to allow the viewer access only to what the artist intends you to see, though in this case, the artist can be anyone. This theme is also very clear in celebrity selfies, mentioned later on. The same ideal of majesty still applies throughout, to anyone, but in particular to celebrities who must maintain an image to keep their followers and power.

This reflects the strategy behind Mirzoeff’s next point, that artists can use self-portraiture for political and social change. In the last century, Cindy Sherman explored the concepts of gender and sexuality through role-playing in various film stills. Through this, she began to challenge social implications or manipulations, such as the superiority of men, all made possible through portraiture and showing others an image which flatly disobeys the common ideals held at the time.

Further movements explored different trends and ideals. After WW1 the concept of self no longer seemed secure and artists like Duchamp fell away from the heroism of the artists or of anyone really, as the entire concept of heroism had changed with the war. Instead of skill or technique making the artist heroic, anything could be art, and one individual self fell away to thoughts of many different selves and more than one perception. Postmodernists called attention to the illusions of life and the misconceptions and also called attention to performance and the reality of life, such as in Nan Goldin’s daily diary of photographs, stitching together an image of her life. The 1990s saw more radical work, especially in LGBTQ spheres, as well as in the topics of race and the altering of perception, at the vogueing balls, the minority became the heroes, just as the artist had done before.

In the modern era, perception can be heavily influenced and blatantly pointed out through photography, as in making fun of the white or male gaze or showing people though a visual medium that their perceptions are false, as in Fosso’s The Chief, which portrays a false perception of African culture and heritage as social commentary. Some have even taken to making unconventional selfies or raising the hashtag “uglyselfies” which, in a way, are a throwback to the realists under Courbet. At the same time, trends and constant social change, along with frequent questions of identity, perception, and performance can change vocabulary, cultures, and long-established themes like portraiture in such ways as the duck face.

Lastly, Mirzoeff explains how Selfies are not intended for individuals, but rather part of a highly networked system. In end effect, they are representations of the art set out for the world to see, and are all about sharing and groups. Selfies are even taken from a close distance, and distance is not introduced to keep the body in the network. While celebrity selfies are posed and a controlled type of performance intended for followers, other selfies are intended for friends or a common circle. These also posed, but some posters do not want them shared or kept, hence Snapchat. As a result of the constant want to share, however, Mirzoeff argues, the selfie is still subject to the male gaze, even if women don’t explicitly dress up for men. At the end of the day, selfies move society towards an increasingly nonverbal form which networked cultures intensify, and this gives a visual form to the global majority’s conversation with itself.

A Commentary:

This section was incredibly interesting to me, and delving into the human psyche and the history behind selfies opened up a lot of doors I had not previously considered. The idea of power, Majesty, and upholding an image is a motivation as old as time, and seeing that in a modern context and on a very familiar level is even more intriguing. As a whole, I agreed with the author on his analysis, though I do believe there is definitely a more attention-seeking aspect to social media as well, and that most of this is done on a very subconscious level, though, analytically and historically, the behavior makes perfect sense. A few things really stuck with me in this section, and I think the ideas would be extremely interesting to explore through video, photography, interview, editorials, and graphic design/infographics.

- Majesty

The Majesty present in the portraits of old is similar to the modern idea of infallibility; in our selfies, it is us as we want to be seen, not as we are, compounded by eternal youth, energy, happiness, and with filters, even beauty, never letting go of the concept of us, the concept of immortality and self importance, or, very fittingly, Majesty. We all like to be kings and queens, no?

- Association

If you are in a selfie with someone, it is similar to the power you gain via association as Velaquez does in Las Meninas. Similarly, if you take a picture with Barack Obama or any singer, say, Ed Sheeran, you gain immediate status as “that person who met (insert name here).”

- Presentation

In a presentation of the artist and their life, in the end, the artist decides what we see. They decide the truth you know and the performance they place before you. People are great actors, especially online. Their lives are cutouts. You only see what you want them to see. The performance then becoming invisible to the world, so that the viewer forgets it is a performance, is the whole idea behind posting and creating an act. It’s like a play on any stage; you don’t want anyone to call you out on it, and you also want the world to see you as you want to be seen, sometimes as you want to see yourself. Though in the spirit of comparison to theatre, on a stage like the Globe, the stakes become higher and it becomes more akin to the game celebrities play on social media.

- Vigeé Le Brun

With the emergence of female artists, especially 1800s Vigeé Le Brun, the artist takes the royal air and transfers it to themselves, making the immortal alongside their work. The thing that struck me about Lebrun’s work, apart from its symbolism, political application, and intricacy, was the way in which it was described:

Look at the camera. Dress fashionably. Show skill in photography and impress others with your portfolio of self worth.

Definition of a modern selfie.

- Cindy Sherman and Nan Goldin

Portraiture as politics has never been too unknown, from paintings of monarchs to political caricatures, but politics and social change through self-portraiture is a very interesting concept to me that I didn’t consider before. Looking and being looked at are important ideas in this sense, and especially in movies, stopping the image can help us understand why we are looking or what is happening, rather than in a grander motion picture, as Sherman does. We as humans often feel feelings for or with others, anxiety, happiness, stress, and pointing out these feelings and reactions in relation to social issues and the portrayal of women in roles of inferiority and objectivity makes the viewer acutely aware of what they do not usually see or consider. In this case, it is not about what the artist does not want the viewer to see, but what the artist does want the viewer to realize. Sherman and Goldin wanted to make a point by putting herself and the viewer in a new position and a new mode of thought.

- Mirrors

I found the inclusion of mirrors very interesting, especially in the work of Velázquez and of Toulouse-Lautrec, having used mirrors in my work as well. What kind of mystique does a mirror add to an image, and is it possible to ask the audience to reflect by using one? Mirrors have a deeper spiritual and historical meaning. Was humankind always obsessed with the idea of reflection and identity? How does this play into modern media? Does this give the so-called “mirror selfie” more value as the subject is using the mirror to “reflect” onto their personality, or is it a painful and ironic juxtaposition, in which the subject does not “reflect upon what they are doing? On a more historical note, would the addition of a black mirror, as in the Mexican obsidian mirror brought to the court of King Louis XIV, be equivalent to a filter? If the normal mirror is already airing the concept of majesty, in Las Meninas, then the new one with a filter adds the a mystique and a magic which was not previously seen.

- The Narrative

There is a narrative to portraiture, and the story can be assumed from it and staged to look a certain way. If you want people to think you’re having fun at the beach, you pose by the water. If you want them to think you’re miserable, you pose in a darkened room or look away from the camera, ashamed. Selfies are never for you. They’re for everyone else. Can design appeal to the vanity of society?

Though looking at another kind of narrative, if selfies are taken in different contexts and in different ways, maybe they are not made in the mainstream and are taken differently, appealing to different audiences and promoting connection through other means. What kind of selfie appeals with which kind of audience? Dramatic? Artsy? Sexy? Impressive? Intelligent? Friendly? How does subconscious connection or rejection work in this way?

- Nan Goldin and the Daily Diary of Photographs

Through her slideshow-esque performance, Nan Goldin’s diary of photographs stitches together an image of her life on a daily basis. In a way, this is exactly what a finsta is, a patchwork of your life which is there for your friends to see. Maybe it is not as carefully composed and portrayed for the viewing of others as a business or regular Instagram might be, but it certainly is controlled. You wouldn’t post a picture of you mad or raging or messing up because that is a part of yourself you probably do not want to amplify in the same way you want to amplify your good qualities (though ironically, an over-amplification of good can turn into a bad quality in and of itself). One of Nan’s photographs does exactly that though. She shows herself battered and beaten, with what look like very serious injuries, letting the audience in to a not-so-pretty part of her life. Needless to say, it was met with shock, but it does make you think about what kinds of stories everyone has and what they aren’t showing, and also makes you wonder how artists and people can control their diaries, not only to show the positive, but also the negative, which, to me shows the power of pictures, performance, and portrayals.

- Impactful Quotes and Commentary

“These reflections and images were a combination of theatre, magic, self-fashioning, and propaganda that were key to sustaining royal power.” (p.39)

This is so close to what Instagram selfies are doing. Take Amy Seder for instance. In every post of herself or with her fiancée, she is perpetuating a royal and perfect image which is untrue to the un-posed form. Her audience, and, in end effect, her subjects, are who she is maintaining her power for, the more followers, the more power.

“As was traditional” (p.47)

The new, exciting, and bold tend to garner the most attention and the most likes, again, look at Amy Seder.

“Whereas for dominant groups the mirror is often a site (and sight) of affirmation, for people who look or feel different, he mirror can be a site of trauma.” (p.48)

This is why people who feel uncomfortable with others seeing them or their lives or don’t feel “good enough” may not post selfies. The mirror is the interface used for Instagram, Facebook, and any other kind of social media. You see yourself reflected, but you have created an image. And this time, the world is watching. But that is exactly what you want.

(Michel Foucalt, author of The Order of Things, about Las Meninas) “…depicting not just what could be seen within it, but the very means of ordering and representing a society…the subject of the portrait is the ways in which it is possible to depict living things in a hierarchy depending on the presence of the king…” (p.35)

Foucault notes that everyone is staring at the center of the painting because the king is standing there, and in a unique twist, this view is also shared by the spectators. This gives an interesting insight into the place where Velázquez worked, and displays the absolutist monarchial themes from the era. The mirror, which he notes, “does not obey the laws of optics so much as it obeys the laws of majesty, much like the painting itself.” (p.35-36)

“Against the fallible individual person of the king, European royalty devised a concept known as ‘the body of the king’, which we call Majesty. Majesty does not sleep, get ill, or become old. It is visualized, not seen. Any action that diminished Majesty was a crime called lèse-majesté…” (p.36)

Consider that we bow to “Your Majesty” and not to the person behind the majesty. Do they become one and the same? Or can the title be shuffled about and re-imagined, draped around the shoulders of whoever wears it better?

- So if we all know it’s performance, why do we still believe it’s real?

Because we’re all acting along. It takes effort to remind yourself that something is not real, especially if the artist is a very good performer, or you do not know them well enough to say for sure what they are like outside their appearance on social media. You like to be the hero of your own story. On a subconscious level, you understand why everyone else wants to be the hero of theirs. In reality, we all like to perform in some way. We all need attention, we all need a story. So you act. So you act along. In this case, through photography, art, and portraiture.

Notable Quotes:

The Principle of the Modern Self

- “The selfie resonates not because it is new, but because it expresses, develops, expands, and intensifies the long history of the self-portrait. The self-portrait showed to others the status of the person depicted. In this sense, what we have come to call our own ‘image’ – the interface of the way we think we look and the way others see us – is the first and fundamental object of global visual culture. The selfie depicts the drama of our own daily performance of ourselves in tension with our inner emotions that may or may not be expressed as we wish. At each stage of the self-portrait’s expansion, more and more people have been able to depict themselves. Today’s young, urban, networked majority has reworked the history of the self-portrait to make the selfie into the first visual signature of the era.” (p.31-32) (It was previously only linked to wealth and power)

- “The selfie is a fusion of the self-image, the self-portrait of the artist as a hero, and the machine image of modern art that works as a digital performance. It has created a new way to think of the history of visual culture as that of the self-portrait.” (p.33)

Your Majesty: Diego Velázquez

- “The Spanish painter Diego Velázquez’s masterpiece Las Meninas (1656) linked the aura of majesty to that of a self-portrait. The painting is a set of visual puns, plays, and performances that revolve around the self-portrait of the artist.” (p.33)

- (Michel Foucault, author of The Order of Things, about Las Meninas) “…depicting not just what could be seen within it, but the very means of ordering and representing a society…the subject of the portrait is the ways in which it is possible to depict living things in a hierarchy depending on the presence of the king…” (p.35)

- “Against the fallible individual person of the king, European royalty devised a concept known as ‘the body of the king’, which we call Majesty. Majesty does not sleep, get ill, or become old. It is visualized, not seen. Any action that diminished Majesty was a crime called lèse-majesté…” (p.36)

- “Las Meninas is invested throughout with this power. Making the image of the king at least the equal, and in some ways the superior, of the king himself.” (p.36)

- “Whatever you believe, the ‘mirror’ shows something that the spectator would usually not be able to see – either the painting that the artist is working on, as Snyder has it, or the King and Queen standing in front of it, as Foucault had it. So the mirror misrepresents, but it also shows a world of possibility. Las Meninas makes a tremendous claim for the power of the artist, both literally and metaphorically.” (p.37)

- “Today, when it is common to see paintings sell for millions, even hundreds of millions, the elite status of the artist is taken for granted. In fact, it is a relatively new and unusual idea that arose first in the imperial nations of the world.” (p.37)

- “Las Meninas plays with what we can see and what we cannot. It keeps out of sight the source of the Spanish monarchy’s power and authority, namely its empire in the Americas.” (p.37)

- “The portrait of the individual who happened to be king also depicted the Majesty of the King, or the power of representation itself.” (p.39)

Your Majesty: Vigeé Le Brun

- “These reflections and images were a combination of theatre, magic, self-fashioning, and propaganda that were key to sustaining royal power.” (p.39)

- “At the same time, by so blurring the difference between the Queen and the artist, Vigeé Le Brun claimed a new level of equivalence between the two.” (p.42)

- The self-portrait with her daughter raised particular issues because women were not even supposed to be artists, according to the received prejudice, so a painting by a woman showing a woman artist was doubly defiant.” (p.42)

- Notably, both the artist and her daughter look out at us confidently, unlike the traditional downcast glance of the Madonna in paintings by artists like Raphael.” (p.42)

Mirror, Mirror On the Wall: Self-Reflection and the Symbolism of the Mirror

- “Mexican artist Pedro Lasch, who has worked with the black mirror, emphasizes that ‘In pre-Colombian America, as in many other cultures, black mirrors were commonly used for divination…The Aztecs directly associated obsidian with Tezcatlipoca, the deadly god of war, sorcery, and sexual transgression.’ If the European mirror image was a place of power, its American equivalent added violence, sexual ambivalence, and storytelling to the imperial mix. In both the pre-encounter Americas and in medieval Europe, the mirror was a place of divination, where fortunes were told and contact could be made with the dead and other spirits. In short, the mirror is a visual bridge between past, present, and future.” (p.38)

- (About Bayard, Self-Portrait as a Drowned Man) “His photograph is what the writer Ariella Azouley has called an ‘event’. It presupposes that the community watching it can imagine the heroic narrative of the author’s suicide and understand his disappointment.” (p.44)

- “Here though, the new medium seems to have influenced the old.” (p. 45) (In relation to Bayard’s Self-Portrait as a Drowned Man and Courbet’s The Wounded Man)

- “Courbet issued a manifesto at his one-man exhibition that year, declaring: “To know in order to be able to do, that was my idea’. In this view, painting, like photography, depicts knowledge and leads to action, or the event. For Bayard and Courbet alike, the artist was the hero, the person capable of creating an event, even at the (fictional) cost of their own life. It is a seductive idea.” (p.45-46)

- Toulouse-Lautrec deliberately painted his reflection in a mirror, rather than just using a mirror to make a self-portrait as was traditional.” (p.47)

- “At the same time, the painting both conceals and reveals the artist…he might have chosen to adjust what he saw, so as to fill the ‘screen’ like a present-day actor or politician standing on a riser to seem taller.” (p.48)

- “Whereas for dominant groups the mirror is often a site (and sight) of affirmation, for people who look or feel different, he mirror can be a site of trauma.” (p.48)

Visual Media and Dramatic Change

- “Visual media was democratized.” (p.39) (In relation to the fall of the absolutist monarchy from 1776-1917)

- “New ways of being came to be imagined and visually represented, including the modern artistic ‘genius’, nearly always male, but also the woman artist.” (p.39-40)

- (In relation to Duchamp and post-WW1 art) “The artist was no longer a hero.” (p.49)

- (In relation to Duchamp and post-WW1 art, especially the readymade Self-Portrait in a Five-Way Mirror) “The ‘self’ no longer seemed so secure. Perhaps there was more than one self in each person…using a hinged mirror, the photo booth created a five-way portrait in three copies.” (p.50)

- “Whereas the heroic modern artist simply depicted her or his own image, the postmodern artist makes him- or herself as their primary project. Nor is this a once-and-for-all remake but it can be done over and over. It is not an event but a performance.” (p.50)

Feminism and Queer Theories

- “‘Eros, c’est la vie’, meaning ‘love is life’.” (p.50)

- “The implication of the portrait, like all drag, is that gender is a performance. Like seeing, it is something we do, rather than something that is inherent and unchangeable.” (p.51)

- “Such public claims to feminist and queer identities as something we do, and can therefore change, combined with the rise of mass personal image-making technologies and personal computing, were central to the creation of the field of visual culture.” (p.52)

- “Men look at the action through the eyes of the male hero and women are obliged to do the same, a form of compulsory gender manipulation.” (p.53)

- “The cinematic gaze also performs the action in which ‘I see myself seeing myself’, that sense that we sometimes have of being looked at, even if we can’t actually see the person doing the looking. For Mulvey and all other feminists, women experience this condition all the time in relation to how they look and act. By freezing the film and making us think precisely about how and why we are looking or being looked at, Sherman made this performance visible…at first, we cannot help but feel anxious on the woman’s behalf. Then we realize…she (Sherman) is using it not to present herself as a victim but to make us aware of the ways in which cinema depicts women as objects to be played with.” (p.53)

- “Photographic self-portraits can also be a diary and a record of what has happened.” (p.55)

- “Goldin warns that we can depict ourselves but it does not always mean we can protect ourselves. While one strand of postmodern art and thought highlighted the illusions of modern consumer society, work like Goldin’s inspired a new generation of artists and writers to concentrate on how gender, race, and sexuality were experienced in everyday life. In a word: performance.” (p.55-56)

- Schechner claimed that all forms of human activity are a performance, assembled from other actions we have taken in the past to create a new whole.” (p.56)

- (In relation to the ballroom, ‘reading’ and vogueing) “In the ballroom, to be read was to fail. It is to be seen by others as they wish to see you, rather than as you see yourself. You wanted to simply appear to be what you appeared to be. In short, for your performance to succeed so well that it becomes invisible as a performance.” (p.58)

- (Butler demonstrated in Gender Trouble) “that ‘gender is the cultural meaning that the sexed body assumes’…what are the categories through which one sees?” (p.59)

- “Judith Halberstam called one such option ‘female masculinity’, the way that some women deploy masculinity as the cultural meaning of their bodies. If we decide a person’s gender by their hair, clothes, and style, it is a visual analysis rather than a scientific deduction.” (p.59)

The Human Race

- “In the same way that Sherman and others have explored how gender is imposed on our bodies from outside, Fosso has visualized how is body is ‘Africanized’ and ‘racialized’.” (p.60)

- (In regards to a deeply racist incident) “Fanon recalled how ‘the Other fixes you with his gaze, gestures, and attitude’. This is a form of photograph, a colonizing power of looking…Fanon felt force to ‘cast an objective gaze over myself, [I] discovered my blackness’. He finds himself seeing himself as the white other sees him – a ‘shade’. He feels fixed, as if ohotographed by what he calls ‘the white gaze’. Under that gaze, he cannot be seen for himself, but only as a set of clichés and stereotypes.” (p.61)

The Modern Selfie

- “In the present moment of transformation, these categories of identity are being remade and reshaped.” (p.62)

- “When ordinary people pose themselves in the most flattering way they can, they take over the role of the artist-as-hero. Each selfie is a performance of a person as they hope to be seen by others. The selfie adopted the machine-made aesthetic of postmodernism and then adapted it for the worldwide Internet audience.” (p.62)

- “It is both online and in our real-world interactions with technology that we experience today’s new visual culture. Our bodies are now in the network and in the world at the same time.” (p.63)

- “The selfie is a new form of predominantly visual digital conversation at one level. At another level, it is the first format of the new global majority and that is its true importance.” (p.63)

- “Despite the name, the selfie is really about social groups and communications within those groups. The majority of those pictures are taken by young women, mostly teenagers, and are largely intended to be seen by their friends.” (p.64)

- “As fashion critics have long asserted, (straight) women dress as much for each other as for men and the same can be said of the selfie. Some have suggested that the premium of attractiveness indicates that the selfie is still subject to the male gaze…the trends for #uglyselfies and to show non-conventional selfies are equally apparent.” (p.64)

- “…there was certainly a moral panic in the media about selfies. A typical comment by CNN commentator Roy Peter Clark declared: ‘Maybe the connotation of selfie should be selfish, self-absorbed, narcissistic, the center of our own universe, a hall of mirrors in which each reflection is our own.” (p.64)

- “Selfies are, like them or not, all about sharing…it’s an invitation to others to like or dislike what you have made and to participate in a visual conversation.” (p.65)

- “Machines are starting to do our seeing for us, using their defaults that we may not understand to shape our perception.” (p.66)

- (In relation to celebrity selfies and emails from important officials) “Both have undoubtedly some oversight role in the product but it is a controlled form of performance.” (p.66)

- “The interest for us is not in the specific platform but the development of a new visual conversation medium, usually relayed by phones that are used less and less for verbal exchange. The selfie and the Snap are digital performances of learned visual vocabularies that have built-in possibilities for improvisation and for failure. Networked cultures are intensifying the visual component and moving past speech.” (p.68)

- “Now we see the digital performance of the self becoming a conversation. Visual images are dense with information, allowing successful performances to convey much more than the basic text message, whether in a single image or short video. The selfie and its other forms like Snapchat have given the first visual form to the new global majority’s conversation with itself. This conversation is fast, intense and visual” (p.69)

- Because it draws on the long history of the self portrait, it’s likely that the selfie in one form or another will continue to play a role in shaping how to see people for a long time to come…shows how a global visual culture is now a standard part of everyday life for millions that takes the performance of our own ‘image’ as its point of departure.” (p.69)

“We don’t see things as they are, we see them as we are.”

— Anaïs Nin

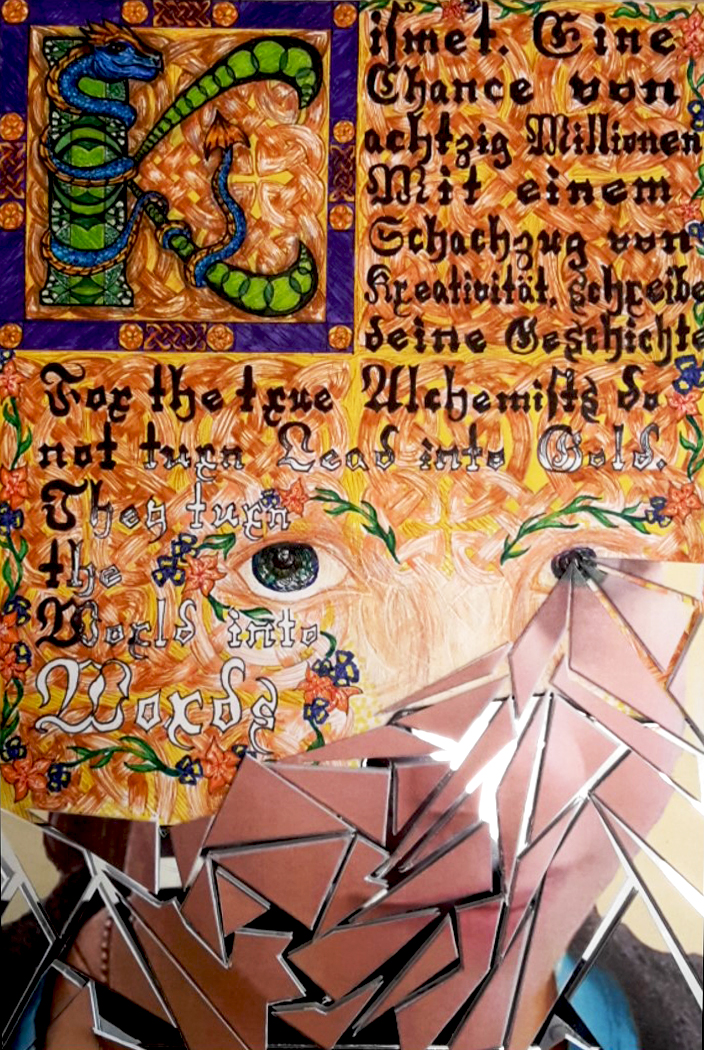

Image Copyright of Karoline Winzer 2018