Chapter two of How to See the World by Nicholas Mirzoeff, deals with vision, the science and philosophy behind how we see, and the way we shape our unique perception and analysis of the world, both individually and communally, culturally and psychologically. This section of the text deals with seven main ideas:

- Vision and seeing are two completely different things; seeing is the symbols we perceive from the world around us and vision is the way we interpret those symbols.

- Visual culture is not just concerned with sight, but with the entire body map.

- You need your brain to see; your mind has the power to interpret and judge the world around you

- Our understood behaviors and empathy for others play deeply into how we see, perceive, and act on a day to day basis.

- Seeing is a shared resource based on learning from ourselves and others, and is forged by the culture we live in and create for ourselves.

- We think in many different parallel layers of thought which communicate and strengthen previous connections. Simply said, even our brains compute.

- There is no purely visual media. Everything has something to do with at least one other sense.

We, as humans, learn mainly as peers and from one another, and the brain is built that way. We are social and visual creatures who learn, well, socially and visually.

A Summary:

Mirzoeff begins by describing that vision is constantly changing, not biologically, but perceptually. In a globalized community we learn how to see ‘better’, and through modern technologies available to consumers, like video games, we become better at noticing certain parts of the world around us. This leads to what the book has termed ‘probablistic inference’, which refers to the kinds of decisions we make based on incomplete information, such as those we make when driving.

The chapter then goes on to explain how it is even possible for vision to exist in such a complex state, namely the difference between seeing and vision. Seeing is what we pick up biologically through the mechanism of our eyes; vision is how we perceive and interpret that information.

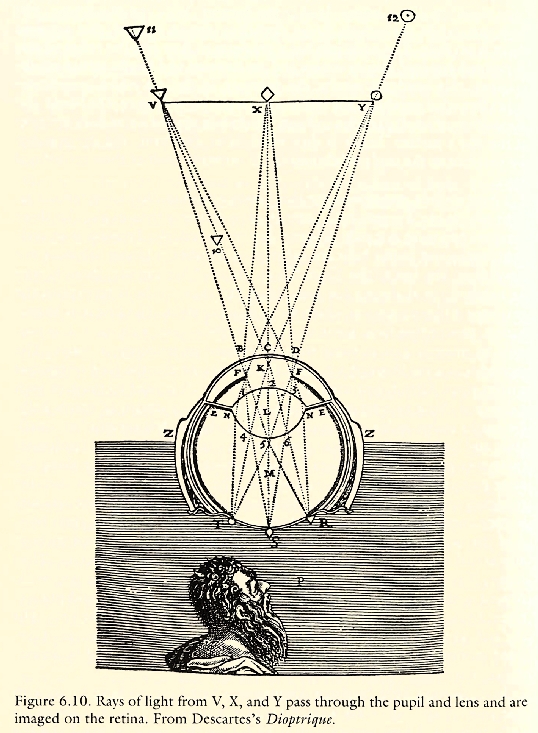

Historically, many different philosophers have taken this into account ad have acted upon the idea that what you see is not always necessarily what is there. The Ancient Greek architects of the Parthenon built an optical illusion into the structure so it would appear straight and seventeenth century western thinkers began to delineate between sight and vision. René Descartes explained that, “judgement corrects the perception of sight,” (p.74) and with his famous sentence, “I think therefore I am,” furthered the idea that thought and sight is what each individual perceives; therefore, everything can be different from what it appears, and everything must be tested and doubted. Descartes also formulated a new diagram dealing with convergence, the eye’s lens, the retina, and magnification complexes, all which are interpreted by a judge at the back of the eye. In short, vision is a judgement of evidence presented to you.

Descartes’s representation of vision.

http://www.faculty.virginia.edu/ASTR5110/lectures/humaneye/humaneye.html

The modern world is finding a new definition for sight and the way it works together with the brain through the field of neurology, which is connected to the computational era. The brain and the way you have been taught plays an immense role in the way in which you see, as evidenced by the Invisible Gorilla test developed by Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris in the 1990s. This experiment was based on not seeing a gorilla in a video because the viewer was focusing on something else, and held that the brain can cause “inattentional blindness”, in which someone does not notice something because they are concentrating on something else. However, Mirzoeff notes, that same test yielded a different result according to who takes it. People from varying classes of visual cultures have extremely different results.

The Invisible Gorilla video.

http://www.chabris.com/Simons1999.pdf

Like animals, who see their world in ways that fir their unique needs, humans see the world in different ways which are unique to us. However, human sight and vision does not evolve biologically through the ages and generations, but rather evolves in a cultural sense, as different cultures and generations grow to see things differently in relation to their occupations and unique needs. For example, in the previous decades, it was desirable to be in extreme focus while being able to avoid distraction, like in machine repair or studying; today, it is in multi-tasking.

MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) Scans are a very good example of mechanical sight and interpretation. The scans have allowed doctors and others to “see” inside the brain and body and to understand its functions and what is wrong (or right) with an individual, but it is still simply a representation created by magnetic fields, hydrogen, and radio frequencies, strikingly similar to our own processing of the world through raw data which we turn into interpretations.

In parallel to artistic and academic development in visual culture, scientists were mapping the brain and the ways in which it sees and comprehends. The 1991 study of Felleman and Van Essen yielded both the discovery that seeing is an interactive process and a map of the different connections in the brain during those events. This map is very similar to a computer in its parallel processing of distinct thoughts and is also very similar to Mondrian’s 1942 Broadway Boogie Woogie, which reflects city life in the jazz era through staccato and bass abstraction.

Fellemen and Van Essen, “Hierarchy of Visual Areas” on left and Mondrian, “Broadway Boogie Woogie” on right.

https://www.piet-mondrian.org/broadway-boogie-woogie.jsp

So in this way, even in our own brains, there is significant computation, and as we think, layers upon layers of meaning are reinforced and added to. In fact, we only see in a stable field of view because our brain computes the constant movement of our eyes and keeps it stable.

Furthermore, Mirzoeff explains that seeing is something we do with great thought and consideration. Our bodies are evolving forms, constantly learning from new experiences and new ideas, even in complete extremes.

This idea of blinking, flickering, and evolving vision can also be seen in photography and art, especially in the comparison between the flickering rococo of François Boucher, the sharp lines of the neo-classical Jacques-Louis David, and the photography of Julia Margaret Cameron, whose portrait of historian and “seer” Thomas Carlisle is blurry, and more effective that way. In regards to the arts and other visual media, the book then goes on to explain that, according to W.J.T. Mitchell, the founder of visual culture studies, “there is no visual media”, meaning that all media uses all sense, which is supported by the network of the brain and also the idea that an artist used a brush and touch to create something you can see.

From left to right: Boucher, Diana Leaving Her Bath, David, Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier and His Wife, Cameron, Thomas Carlisle

Mirzoeff then explains what neuroscientists refer to as ‘body maps’, which encompasses an entirely different level of seeing where you are in control of and in coordination with your body. These body maps are highly sophisticated and lead to proprioception, or, “a sense of the relative positioning of all the different parts of your body.” (p. 92). In turn, it is possible for individuals to draw wildly different perceptions from their body maps, for example, those with anorexia and those who are addicted to hallucinogens. However, body maps can be reimagined and relearned, which speaks to the power of the mind.

The chapter ends with the explanation of so-called “mirror neurons” and of the idea that we, as humans, learn socially. Mirror neurons produce the same effect in our own brain as what we are watching, blurring the line between you and the other person because the brain can’t tell the difference and we feel as if we were doing what the other person is doing. As an offshoot of this concept, we really do much of our learning, especially visually, with others, and rarely by ourselves, creating a visual culture which is collective and shared by our unique, yet common perceptions.

A Commentary:

This section was interesting in that, simply, we do not see with our eyes. Eyes are the mechanism through which the brain sees, and this leads to a host of new ideas involving perception, the brain patching together which is, in essence, a constant panorama, and how the way we see the world, both through sight and vision.

- The Rapidity of Seeing

As Mirzoeff states, there are three different kinds of unconscious eye movement involved in seeing: convergence movements, which direct the eyes to one place, pursuit movements, which track moving items, and saccade movements, which rapidly scan an area, either voluntarily of not, and allow you to pick up data points. In this way, the phrase ‘fixing your gaze’ is a complete misconception. We as humans are always moving, always watching, always collecting data. This can lead to a major data overload, but it can also help us better understand our surroundings. The question then in relation to GMD is how do we think about seeing? What makes us look up? What makes us watch? These are important questions to ask in any firm or advertisement agency, but is also very important to understanding the world: how the news enthralls us with something that makes us look up and how that can lead to situations like the Trump election in the U.S., how social rights movements call attention to themselves, and how to make your message heard by the right people, no matter who you are.

2. Thought and Thinking

Our thoughts build in parallel pathways and move back and forth with insane speed and connection. But through this, even in our own brains, there is significant computation, and as we think, layers upon layers of meaning are reinforced and added to. Incredible. But then…is even an artist’s mind, in the end, computational in the way an engineer’s might be? Or do we all think in slightly different ways and pathways too? Are we all good at everything and gravitate towards a focus or do we have a predisposition to how our brains are wired? Do we find a different use for the same pathways?

3. I Think Therefore I Am

What does this mean for design? Can designers manipulate and influence the world to have certain cultural, political, and social connotations? How? Does thinking, overthinking, and thinking against the grain sometimes even constitute danger?

4. I Perceive Therefore I Am

We use our brain and our eyes in conjunction so often that we do not really see something, we perceive symbols and data and classify it. So in truth, it is our minds which are really doing the seeing. This is why we all see different versions of the same color or know it by different names.

5. Proprioception

Proprioception is defined as “a sense of the relative positioning of all the different parts of your body.” (p. 92). As the book explains, for example, you swat a fly away, but not hard enough to hurt you too. Incredibly, we have a very good sense of our own bodies. Mentally and physically, we tend to make sure we are not harmed, and the interconnected systems of nerves, thoughts, touch, and sight control that you are never able to accidentally hurt yourself. This is a very interesting idea in that you are always aware of yourself in ways that you do not typically thing about. How does this influence the way we notice or see ourselves? How does this play into our perceptions and personal triggers about weight, our surroundings, people in the vicinity, and our own lives and daily interactions? How does this influence sight?

6. Focus

Photographers disputed the idea of crisp lines being the “correct” focus, especially Julia Margaret Cameron, whose portrait of historian and “seer” Thomas Carlisle is blurry, and more effective that way. Focus is something which is unique to each situation. This is where the blurred lines of artistry come in; when do you make something “perfect” and “correct” and when do you play with the deeper meaning behind the image?

7. (R)evolution of Sight

Our bodies are evolving forms, constantly learning from new experiences and new ideas, even in the harshest extremes. The beauty of the human condition is that we always somehow manage to step into the unknown, into the fog that surrounds our comfort zone, and somehow, we always think the world will end – but it never does. This is what makes risks so interesting in regards to art and life in general. Once you understand that life keeps going, even if you screw up or try something that does not work, you become much more open to the possibility of the impossible.

“What if I fall? But oh my darling, what if you fly”

8. The Invisible Gorilla Test

“Roughly half the people watching did not even notice the gorilla. They were concentrating on counting.” (p.77)

Purely on a linguistic basis, there is a very interesting idea in this quote. Notice that you can’t use the word “see” in place of the word “notice” because when you start differentiating between sight and attention, it becomes very tricky.

The idea that the test yielded a different result according to who takes it is also extremely intriguing in regards to the Invisible Gorilla test. The original test found that many did not see the gorilla, but once different visual cultures were introduced later, such as people how cold play basketball and younger individuals who were very used to multitasking, the pattern completely changed. This really speaks to perception and the idea that different people see different things. People are trained by their past; those who knew quite a bit about basketball noticed the gorilla immediately, and those who played video games and watched videos were more trained toward seeing it. People are also trained by their era. If it is desirable to know how to multitask, teaching systems, students, and educators will begin to follow the trend, and vice versa for individualized focus. The mind is an extremely powerful tool; by just changing mindsets, we see the world so much differently. In truth, it has always been this way; the British Georgians made themselves as pale as possible, because it was desirable at the time to be extremely pale, models are typically tall and skinny, because it is what the market leans towards, and overall, the allure of the “queen”, I believe, has definitely contributed to the trend of “female beauty” as being pale and slender throughout European history; if you did not have to work in the fields like a farmer, you will not have developed muscles or skin tones in the same way, alluding to a lifestyle of power and luxury, and thereby to a more “regal” look.

9. Notable Quotes and Commentary

“Seeing the world is not about what we see but about what we make of what we see. We put together an understanding of the world that makes sense from what we already know or think we know.” (p.73)

- This is why perception varies so much, and this is also why we tend to patchwork information together to form different opinions or judgements. Every indicator means something to you, and, when presented with all of your individually mandated facts, you patch together your own version of the puzzle, whether right or wrong or neither. In this sense, however, there really is no right or wrong, there is only right and left. Validity is lent by others with the same view as you, and those who do not share that view, or the coalition of which they are a part of, are, in your mind, wrong. However. They may think the exact same of you, so with a flipped script, the story reads markedly different, yet archetypally the same.

“First used to communicate with ships, radio became a popular format in the 1920s. Now, however, it is our own bodies that are the transmitters. As we cannot interpret these waves unaided, the MRI machine converts them into visual form. These are not images, however, in the sense that they are representations of something seen. The scanned organ remains inside the body, unseen by anyone or anything. Like any other picture produced by a computer, MRI scans are computations, not images.” (p.81)

- Is the designer a kind of amplifier for human vision as the MRI is one for representation? This quote also goes back to the initial idea that we live in a very visual culture. We do better, as a whole, thinking in a non-linear path and understanding in a visual form. Is this then also similar to Instagram? MRI scans are computations which show us a representation of something we cannot personally touch or know, and Instagram images are photos taken by a camera or phone through a digital machination which represents the lives of people we may not really know.

“What we call vision happens in the set of feedback and parallel processing that takes place between [the retina] and the hippocampus…clearly, vision is not just a case of light entering the eyes and being judged, as it was for Descartes. It is a back-and-forth shuffle with twists and turns, creating a vibrant sense of rhythm in the image.” (p.84)

- Is this why humans are so drawn to rocking, rhythm, and pattern? Would this be an important principle of design to keep in mind when designing for understandability and cohesiveness, as in infographics?

(In relation to Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie Woogie) “In the painting, the combination of repeated bass rhythm and staccato dance movements evocatively conveyed the affect of the machine age.”

- This also shows how science, culture, and visuals all grow together, often one in response to another, and sometimes even inspired by or as a cumulative whole.

“Indeed, it is noticeable that people today often put more trust in a less-than-perfect photograph or video that takes an effort to decipher then they do into a professionally finished work, because they suspect that the latter will have been manipulated.” (p.90)

- This brings us back to the question of selfies and the knowledge that many magazine pictures are manipulated. Why do we care so much when the photographs are not of people?

“That is to say, we don’t ‘see’ color, shape or speed so much as work out what they must be.The brain is not a camera. It is a sketchpad.” (p.94)

- This is why no one has come up with making a camera that captures exactly what you see. Everyone sees differently and in the end, it is your mind which creates the picture, and your perception which shapes it. Does this mean that what the camera sees is closer to reality than your own vision?

“…the brain is effectively a shared space with a ‘we’ that is not a crowd of individuals but a collective formation. It is from this formation that individuals emerge, meaning that we move from the social to the individual…we don’t generalize what we learn on our own, but apply the general to the specific, because we all form a ‘theory of mind’. Such a theory, well known to philosophers, is vital to human interaction because without it, no one could even begin to imagine how others might act. Like all visual culture, this insight is rooted in the everyday.” (p.95)

- Similarly, we apply the general patterns of the face to recognition, if we did not, we could never recognize one another. Our personal perceptions may also play into why we can recognize some people and not others; for example, how a group of people may look so similar und un-differentiable to you, but they can tell each other apart with ease and not be able to do the same to you.

Notable Quotes:

How We See

- “The point here is that we do not actually ‘see’ with our eyes but with our brains.” (p.73)

- “Seeing the world is not about what we see but about what we make of what we see. We put together an understanding of the world that makes sense from what we already know or think we know.” (p.73)

- “In short, seeing is a very complex and interactive process. It does not, in fact, happen at a single place in the brain, as the first ‘lighting up’ images had suggested, but all over in a rapid series of back-and-forth exchanges. Further, this interactivity between the visual zones of the brain and their associated areas happens at a series of ten to fourteen hierarchical levels. That is to say, seeing is not a definitive judgment, as we had once assumed, but a process of mental analysis that goes backwards and forwards between different areas of the brain. It takes a brain to see, not just a pair of eyes.” (p.82)

- “We should think of looking as a whole as a form of doing, or a performance…we make a world in which the way we look makes sense and enables the actions we want to perform. And it is also a form of computing because we use that model to calculate how to be active in that world.” (p.87)

- “There is more processing space in the brain devoted to vision than all the other senses combined, which might account for why this illusion is so irresistible.” (p.93)

- “It turns out, according to recent research, that this is because there are two ‘streams’ of brain activity: one for perception and one for action (Nassi and Callaway 2009). Vision is a plural noun, it appears. One stream (perception) recognizes a friend. The other (action) reaches for their hand and shakes it.” (p.94)

- “That is to say, we don’t ‘see’ color, shape or speed so much as work out what they must be. The brain is not a camera. It is a sketchpad.” (p.94)

The History of Sight

- “The ancient Greek architects of the Parthenon in Athens designed the sides of their columns with a slight outward curve (entasis) as they rose in order to convey the appearance of being perfectly straight.” (p.74)

- “…light was held to be divine and so not subject to human understanding.” (p.76)

- Vision was understood as a courtroom, in which the eye presents evidence for the judge to decide (There was no jury, as in the French courts of the time.)” (p.76)

- “An MRI scan is actually an exercise in the history of media. Magnetism and its relation to electricity was a fascination for nineteenth-century science.” (p.80)

- “First used to communicate with ships, radio became a popular format in the 1920s. Now, however, it is our own bodies that are the transmitters. As we cannot interpret these waves unaided, the MRI machine converts them into visual form. These are not images, however, in the sense that they are representations of something seen. The scanned organ remains inside the body, unseen by anyone or anything. Like any other picture produced by a computer, MRI scans are computations, not images.” (p.81)

Neurology and the Progression of Perception

- “…neurology, a fast-developing part of biological science, sees the body and mind as integrated systems and people as communal social beings connected by empathy. The metaphors here are not taken from the courtroom but from computer networks…according to this perspective, we learn how to become individuals as part of a wider community.” (p.77)

- (inattentional blindness) “the inability to perceive outside information when concentrating on a task” (p.77)

- Roughly half the people watching did not even notice the gorilla. They were concentrating on counting.” (p.77)

- “…neuroscience and its ways of visualizing the mind and human thought are becoming the vital visual metaphors of our time. It is our version of the truth, for better or for worse.” (p.77)

Change and Challenges

- “Maturana stressed that living things change themselves because of their awareness of their interactions with the outside world, not just in the very long run described by evolution, but as a condition of day-to-day existence (Maturana 1980).” (p.79)

- “Rather, the change comes in the way we make use of visual information. Today, we prioritize the ability to keep in touch with multiple channels of information – multi-tasking is the popular term.” (p.79)

- “…people have always known in some way that vision is constantly being learned and relearned.” (p.94)

Sight and the Progression of Art

- “What we call vision happens in the set of feedback and parallel processing that takes place between [the retina] and the hippocampus…clearly, vision is not just a case of light entering the eyes and being judged, as it was for Descartes. It is a back-and-forth shuffle with twists and turns, creating a vibrant sense of rhythm in the image.” (p.84)

- (In relation to Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie Woogie) “In the painting, the combination of repeated bass rhythm and staccato dance movements evocatively conveyed the affect of the machine age.”

- “If we take the liberty of making a formal comparison between this painting and the 1991 depiction of vision (recognizing that they come from very different contexts), we can see in both cases how vision has gone from being the single decision imagined by Descartes to the dynamic experience of the modern, machine-based city, conveyed by its flickering lights, back and forth journeys, and infectious music.” (p.85)

- “Vision now seems more akin to the puzzling one does in front of a complex painting like Las Meninas – the moving back and forth to gain different effects, the homing in on certain details, the changing effect that often returns to the beginning point – than it does to the instant affirmation of photography.” (p.87)

- (In relation to Diana Leaving Her Bath) “A ‘blinking’ vision is aware of its effort to see, of the difference between it and what it is trying to see, and even the eyelid that comes in-between the two.” (p.88)

- (In relation to neo-classical painting) “This realism wanted to efface all flickering and insist that what we see is what is there and nothing else.” (p.90)

- (In relation to the two paintings by Boucher and David) “Rather, what these works of art reveal is that the current research fits into a well-established line of thought about vision, even if it is based on very different evidence and in a very different context.” (p. 90)

- “Indeed, it is noticeable that people today often put more trust in a less-than-perfect photograph or video that takes an effort to decipher then they do into a professionally finished work, because they suspect that the latter will have been manipulated.” (p.90)

Computation and Parallel Process

- “It is possible to imagine a species that could hear those frequencies and detect what is wrong (or not) with the person being scanned. Humans need to see something.” (p.80)

- “In this mapping [referring to the “Hierarchy of Visual Areas” by Felleman and Van Essen] the neural pathways for each sense are distinct but are processed in parallel, like a computer. Their understanding of vision shows it as a set of feedback loops.” (p.83)

- “The information goes back and forth from one level to the next, filling in pieces as it goes. So, it is (for now) settled: seeing is something we do, rather than something that happens naturally.” (p.86)

- “From that point, information is distributed and processed in a series of parallel steps that continuously reinforce the other layers. What we used to call an image is no known to be a computation, even in the brain.” (p.86)

- (In regards to the three types of unconscious eye movement) “The resulting ‘image’ that we ‘see’ remains stable because the brain computes it in that way.” (p.86)

The Connection

- “We continuously rework these systems, absorb information, and change the way we perceive in order to account for it…our minds and bodies are continuously interacting, forming one system.” (p.87)

- “Now we can reinforce that interpretation with the understanding that perception is not a single action but a process carefully assembled within the brain. That work centers on what neuroscientists call ‘body maps’, our sense of where and who we are.” (p.91)

The We

- “…we do indeed learn mostly from each other, rather than by ourselves, and that our brains are specifically designed for that purpose. Sense experience is not individual but common.” (p. 94-95)

- “The quality of empathy is, in the current metaphor, hard-wired.” (p.95)

- “…the brain is effectively a shared space with a ‘we’ that is not a crowd of individuals but a collective formation. It is from this formation that individuals emerge, meaning that we move from the social to the individual…we don’t generalize what we learn on our own, but apply the general to the specific, because we all form a ‘theory of mind’. Such a theory, well known to philosophers, is vital to human interaction because without it, no one could even begin to imagine how others might act. Like all visual culture, this insight is rooted in the everyday.” (p.95)

- “Rather than being a distraction from reality, the imagination is key to our very understanding of how we exist in the world.” (p.96)

- “In short, mirror neurons do not only allow me to see the world from my point of view, but to visualize it from the point of view of others.” (p.96)

Visual Culture and the Collective

- “As Ramachandran points out, humans are exceptional because we develop so slowly, learning everything from basic motor skills to language after birth, unlike most animals: ‘Obviously we must gain some very large advantage from this costly, not to mention risky up-front investment and we do: It’s called culture’ So it would not be unreasonable to say that the collective theory of seeing we develop would be something that we can call ‘visual culture’” (p.95)

- “As part of the interfaced sensory apparatus of the brain, visual culture is not only visual (in the common-sense meaning of the term) but it is also concerned with the entire body map.” (p.95)

- “The final implication is that humans have developed in the dramatically rapid way that we have, not only by Darwin’s natural selection, but also though cultural development.” (p.95)

- “All of the experience we call ‘vision’ is multiply processed, multiply analyzed and subject to constant feedback from other areas of the body, rather than being a single, independent ‘sense’.” (p.95)

- “Because seeing is a specific instance of our collective theory of mind, vision is a commons, meaning a shared resource that we can nonetheless make use of in ways that also suit our individual needs. And this is what visual culture seeks to debate, explore, and explain.” (p.97)

Cover photo courtesy of https://www.acts.de/en/company/our-vision/.